Richard Wagner's (1813-1883)

Der Ring des Nibelungen is comprised of what Wagner called "music dramas":

- Das Rheingold (The Rhine Gold)

- Die Walküre (The Valkyrie)

- Siegfried

- Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods)

Wagner not only wrote the music, but also wrote the libretto of this extraordinary opera cycle. It took him over 25 years to compose, and he intended the work to be performed as a series over the course of four evenings. In total, the length of "The Ring" is approximately 15 hours. Taken form Norse legends, the ring cycle tells the stories of gods and heroes as they struggle to secure a ring that grants supreme power over the world. Musically,

Der Ring des Nibelungen is a masterpiece built of beautiful melodies in a dense and rich texture. Wagner expanded chromatic harmony and blurs the lines of functional harmony. Scored for a large orchestra, the choice of instruments Wagner made are on equal footing with the melody, harmony, libretto, staging, etc... All of these elements combine to support the drama of this work -- a

gesamtkunstwerk or "Total work of art."

Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen

by Topi Ylinen

I. Das Rheingold (The Rhinegold)

The Three Rhinemaidens are swimming in the depths of the river Rhine, as Alberich the Nibelung (a night-dwarf) enters. The Rhinemaidens tease him as he tries catch them.

Then a ray of sunlight shines on pile of gold. The Rhinemaidens tell Alberich that if someone should forswear all love, he would be able to forge an all-powerful ring of the Rhinegold. They tell this to Alberich because they think he would never forswear love, as he was so lustily chasing them. But they are wrong: mad with despair, Alberich forswears and curses all love and he steals the Rhinegold and flees before the shocked Rhinemaidens can take any action.

Elsewhere, Wotan (Odin, the chief of gods) has hired two giants - Fasolt and Fafner - build him a mighty fortress. Following the cunning Loge's advice, he promised the giants goddess Freya as payment. Now Freya is fleeing towards Wotan and his wife, Fricka (goddess of marriage), as the giants appear: the fortress is completed and they want their payment. Wotan tries to play time and hopes Loge would appear and find some clever way out of the nasty situation. Donner (Thor) and Froh arrive to protect Freya. Donner is about to swing his hammer at the giants, but Wotan stops him: Wotan's Runespear protects his deal with the giants.

Just then Loge appears in a flickering flame. All gods are angry at him. Loge says he understands the giants' demand - for who could deny a woman's charm? Who except Alberich? And so Loge tells them about Alberich and new might: the Ring and the treasures he has acquired by the power of the Ring. Alberich is a bitter enemy of the giants and the two giants declare that they will take the Nibelung's treasure instead of Freya. As Wotan hesitates, the giants take Freya away and demand their payment be delivered before sunset. The gods suddenly feel weak: Loge knows that this is because Freya normally gives them Golden Apples which bestows them their eternal youth - no Freya, no Apples. Loge suggests that Wotan should take the Ring from Alberich, since it does not belong to him: steal from the thief. Left with little choice, Wotan agrees to try to win Alberich's treasure. He tells Loge to lead him to Nibelheim, but not through the river Rhine (possibly because he does not want the Rhinemaidens to see him, as he does not intend to return the gold to them but keep it).

Incidentally, the Rhinemaidens may be his daughters, although there is no evidence whatsoever in the text that Wotan is the father they referred to.

Meanwhile, in Nibelheim, Alberich has forced his brother, Mime, forge a magic helmet called the Tarnhelm, which enables its wearer to change shape and to become invisible (it also grants its wearer the ability to teleport, but this will be revealed much later). Mime has hidden the Tarnhelm, hoping to steal the Ring with its help, but he fears Alberich's might too much and gives the helmet when Alberich asks for it. Alberich wears the Tarnhelm and turns invisible - and beats poor Mime up.

Alberich has just left when Loge and Wotan arrive. They hear latest news from Mime and Loge promises Mime they will free all Nibelung dwarfs from Alberich's tyranny. Alberich arrives and becomes visible. He recognizes Wotan and Loge immediately and asks what is their business here. He is told that the gods have heard of his new might and wanted to see if the rumours are true. Alberich boasts with his great treasures with which he says he will rule the world. Loge pretends disbelief in the Tarnhelm's powers, and to prove its might, Alberich wears the Tarnhelm and turns into a huge dragon (serpent?). Loge pretends to be frightened, and asks next whether Alberich could turn into something tiny to evade his enemies. Alberich doesn't see the trick and turns into a toad. Loge tells Wotan to catch the toad: the gods seize the Tarnhelm and leave Nibelheim with Alberich as their captive.

Wotan demands that Alberich pay all his treasures as a ransom before he can be freed. Alberich summons the Nibelungs and they pile all his treasures. Loge also places the Tarnhelm on the pile, Alberich is furious, but tries to calm himself with the knowledge that Mime can forge a new magic helmet. But then Wotan demands the Ring as well. He proceeds to take it and lets Loge free Alberich. Crushed, Alberich places a powerful curse on the ring: whoever has the Ring will be its slave and is doomed, he will be envied and hated by others - everyone will covet for the Ring. With these words he leaves. Wotan ignores his words.

The giants return with Freya. They demand that the treasure must fully cover Freya before they are satisfied. After all gold has been used, her hair can still be seen: the Tarnhelm must cover that. Even then, Fasolt claims he can still see Freya's eye - but he can also see a golden ring on Wotan's finger: he wants it too. Wotan refuses abruptly. The giants say the deal is off.

Just then, bathed in blue light, a woman appears and tells Wotan to surrender the Ring and thus evade its dread curse. She introduces herself as Erda the Earthmother and tells the gods she has seen a dark day dawn for the gods: the End of Everything. Then she disappears. Reluctantly, Wotan follows this piece of advice and gives the Ring to the giants.

Immediately, the giants start a fight over how to divide the treasure. Fafner kills his brother Fasolt, and gets all the treasure. The power of the curse horrifies Wotan. After Fafner has left, the gods turn to greet their new home. Donner summons a lightning bolt to clear away the fog and a Rainbow Bridge spreads out. Wotan is silent for a moment, as though seized by a novel idea. He christens the fortress Valhalla.

As the gods are walking the Rainbow Bridge to Valhalla, Loge stays behind them and remarks (aside) that they are merely hastening to their own end and he would welcome the day he can turn again into his elemental (form) and burn everything. Then, distant singing can be heard: the Rhinemaidens mourn their lost gold. Wotan bids Loge tell them to be silent - but they won't be silenced. The gods ignore the Rhinemaidens and enter Valhalla.

II. Die Walküre, (The Valkyries)

Act 1

There is a thunderstorm. A weaponless man called Siegmund is fleeing and comes across a house: he is wounded and exhausted and cannot go on, so he decides to rest here. (It is possible that Siegmund does not know his own name yet). Sieglinde, who lives in the house, finds him and gives him water. She informs him that the the house and she herself belong to Hunding and that the guest should wait for the master of the house. Siegmund says that bad luck haunts him and that he must leave lest he should bring bad luck to the house but Sieglinde bids him stay: he cannot bring bad luck where bad luck already lives. Siegmund names himself "Woeful" and waits for Hunding.

Hunding arrives and greets Siegmund in a formal manner and then wants to hear his story. Siegmund tells his father was "Wolf" (he wore a wolfskin), and he had a twin sister. "Wolf" was very warlike and had many enemies. As Siegmund one day returned home, his mother had been killed and the home burned. His sister and father were nowhere to be found. He only found an empty wolfskin in the forest. Later he saw a damsel in distress: she was being forced into a marriage he did not want. Siegmund rushed into her defence and killed some of her enemies - only to learn they were actually her brothers and kinsmen. Siegmund fought, but was wounded and eventually lost his sword. The girl was killed and Siegmund had to flee.

Now Hunding declares that he was summoned to avenge on a murderer who had killed some people nearby and Siegmund turns out to be that murderer. Hunding says that his house will protect "Woeful" for today but that he must prepare to fight Hunding to the death tomorrow. Then he retreats to his bed - and Sieglinde mixes him a drugged drink, which will make him sleep heavily so she can meet Siegmund in private.

Siegmund is left alone. He remembers his father (whom he now calls "Volsa") promised him a sword when he most badly would need one - where is that sword now he asks. Sieglinde enters. She tells him she was forced into marrying Hunding against her will. Their wedding party had an uninvited guest: a fearsome stranger whose large hat was pulled down to cover one eye. Everybody except Sieglinde were afraid of him. The stranger had a sword and he thrust the sword in the tree trunk that is in the middle of Hunding's house and said that the blade would belong to anyone who pulled it out of the tree. Many have tried but none of them succeeded. (The appearance of the Valhalla leitmotif here makes it clear that the stranger was Wotan - just as he was "Volsa"). Sieglinde believes Siegmund is this person: the hero who would free her from her miserable life as Hunding's property.

They both reveal their true feelings to each other. Sieglinde reveals to Siegmund that she is his lost twin sister as well, and calls him his true name, Siegmund. Siegmund draws the enchanted sword from the tree and names it Nothung ("Needy"). They embrace each other passionately and the curtain falls.

Act 2

Wotan is giving orders to his valkyrie daughter Bruennhilde: she is to protect Siegmund in the fight that will come soon. Just then Fricka arrives and starts to complain: she, as the guardian of the wedlock, is furious at Wotan's latest stunt. She was alarmed by Hunding's prayers to her, but Wotan says he does not honor Hunding's marriage since it was against Sieglinde's will. Now Fricka says the trouble is not only that but - she asks - when has anyone heard of twin-born lovers! Wotan answers abruptly: you are hearing of it now. But Fricka insists that it is the gods' status and honour that is at stake: should they lose the mortals' respect, they would lose their power.

Not even Wotan's explanations can change her mind: as Wotan calls Siegmund a "free hero", she quite rightly points out that Siegmund not free nor independent at all [since it was Wotan - posing as "Volsa" - who brought him up, and led him to the "Wotan Sword" (as it is called by Mime in the opera)] and she demands that Wotan withdraw all protection and even the magic sword from Siegmund - and finally makes Wotan give his promise of that.

Fricka leaves as Bruennhilde enters and finds her father looking gloomy. Wotan tells her his tale: how Loge tricked him into dishonest treties concealing evil, how they stole the Ring and how he was warned by Erda. Later Wotan visited her again "in the bowels of the earth" and overpowered her with the magic of love. Erda gave him information but as a price bore him Bruennhilde the Valkyrie [though the other 8 Valkyries are her "sisters" and quite equal in status and powers, they may have a different mother - this would explain Bruennhilde being Wotan's favorite child]. Wotan sent the valkyries to collect perished brave heroes into the halls of Valhalla to avert the horrible end Erda foretold. Alberich's army could not beat Wotan's heroes, but if Alberich regained the Ring, he could turn Wotan's heroes against him. Fafner is guarding the Ring now, but Wotan's own treaties prevent him from attacking Fafner directly. Thus, the only possible solution for him is to let a free hero kill Fafner - Siegmund was to be this hero, but as Fricka remarked, Siegmund was everything but free. Wotan has no idea what to do now. He even knows the end is near for Erda said that when Alberich has a son, the end will come soon: now he has learned Alberich has bought a woman with gold and that woman is now pregnant with Alberich's child.

Wotan orders Bruennhilde to protect Hunding instead of Siegmund, but Bruennhilde - feeling as compassionate toward Siegmund as Wotan himself - refuses. Wotan is angered by this: he furiously orders Bruennhilde to ensure that Siegmund dies. Bruennhilde can only obey.

Siegmund and Sieglinde are desperately fleeing Hunding and his kinsmen who are hunting them with dogs. Sieglinde gets hysterical and faints. Then Bruennhilde appears and announces to Siegmund that only those doomed to die may see her - he is to follow her to Valhalla. But as he learns he will not find Sieglinde in Valhalla, Siegmund refuses Bruennhilde's promises. He decides he'll rather kill himself and Sieglinde with one swift blow than let Hunding get them. Bruennhilde is so moved by his courage that she decides to rebel against Wotan's orders and protect Siegmund.

When Sieglinde awakens, Siegmund has already left to face Hunding: she can hear their voices but cannot see them. Hunding and Siegmund fight, after a few insults. As they fight, Bruennhilde appears, holding a shield above Siegmund and tells him trust his sword. But then Wotan appears, in a red storm cloud and breaks Nothung into pieces with his spear. Hunding finishes Siegmund off easily, Bruennhilde flees with Sieglinde on her horse's back.

Wotan gazes thoughtfully Siegmund's corpse and then turns to Hunding who is gloating over his victory. He gives Hunding one contemptuous gesture and Hunding falls down dead. Then he turns to chase Bruennhilde, the rebel, who dared disobey his order and leaves with thunder and lightning.

Act 3

Eight of the Valkyrie sisters are bringing dead heroes on their horses, when Bruennhilde appears with Sieglinde, asking for a horse for Sieglinde (her own horse, Grane, faints after a strenuous ride). The other valkyries are shocked when they hear she has disobeyed Wotan. They refuse to give Sieglinde a horse, but when Schwertleite tells Bruennhilde that Wotan seldom ventures eastwards, where Fafner guards his treasure in the form of a dragon, Bruennhilde thinks it would be the safest place for Sieglinde. She gives her the splinters of Nothung and tells that she is carrying the greatest hero of all time in her womb and she is to name him Siegfried. Sieglinde flees just before Wotan arrives in a thundercloud.

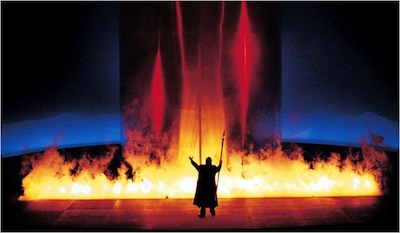

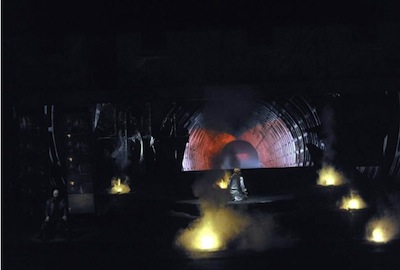

Bruennhilde is terrified behind the backs of her sisters - but finally comes out of her hiding. Wotan is furious: he says Bruennhilde will be a valkyrie no longer, she will lay defenceless in deep sleep and will become wife to the first person who finds her. The other valkyries protest, but Wotan tells them to leave lest they wish to share Bruennhilde's fate. The eight valkyries flee in terror, only Bruennhilde and Wotan are left. They have a talk: Bruennhilde tries to make Wotanchange his mind, but it is no use. Her last wish is that Wotan surround her with a wall of fire which only bravest of all heroes can penetrate. Wotan says she's asking too much, but as Bruennhilde asks him to rather kill her on the spot, he is moved so deeply that he decides to grant his daughter's last wish, after all.

Bruennhilde falls in deep sleep and Wotan gives her a long goodbye - and then kisses her godhood away: she is a mortal woman now. Wotan knocks the ground three times with his Runespear and thus summons Loge (in his fire-elemental form) to surround the sleeping Bruennhilde. He leaves the scene with the words "Whosoever fears the tip of my spear shall never pass through the fire!"

III. Siegfried

Act I

In a cavern in deep wilderness, Mime the dwarven smith is forging a sword. He is frustrated: no matter how good a sword he forges, his young "ward" Siegfried breaks every one of them. There is only one sword Siegfried could not break: Nothung the enchanted. But Mime cannot forge it anew. In his monologue we learn that he wants Siegfried to slay Fafner (who is now a dragon) so he could get the Ring.

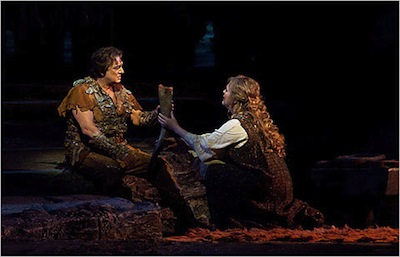

That's when Siegfried arrives, riding a bear he has tamed: Mime is scared stiff. Siegfried asks for a sword and Mime hands him his latest piece of forging. Siegfried lets the bear go and studies the sword, but he breaks it saying that a sword must be hard and firm, not a puny pin. Siegfried also refuses the food Mime offers him, saying he has roasted meat for himself. Next he makes an inquiry about his parents: he saw that all animals have two parents, and Mime cannot be his since he looks so different. Pressed hard, Mime finally tells him he found his mother as she gave birth to him in the wilderness and died. He says he does not know Siegfried's father's name (this claim is obviously untrue, see later). Finally Mime shows Siegfried the fragments of the sword Nothung as a proof of his tale. Siegfried tells him to forge Nothung again so he can leave Mime forever. He exits, telling Mime to be ready when he is back.

Mime is alone, worrying about his plans which do not seem to work, as Wotan enters, disguised as "Wanderer". Mime is terrified: he wants to get rid of "Wanderer", but Wotan stubbornly sits down and challenges Mime to a riddle game. Wotan wagers his head and Mime is to ask three riddles - he must answer all three correctly to redeem his head.

First Mime asks the name of the race that dwells in the earth's depths. Wotan answers correctly Nibelungs. The next question is the name of the race that dwells on the earth's face - the Giants. Mime's last question is which race lives high in the clouds, and Wotan answers correctly: the gods. As he tells Mime about them, he by "mistake" lets his Runespear knock the ground: there is thunder and lightning - Mime cowers. Now "Wanderer" tells that since he wagered his head, Mime should have asked things he needed to know instead of such meaningless riddles. Now Mime must answer to three riddles of his or Mime's head is his! First "Wanderer" asks the name of the race Wotan oppresses though he loves them very much. This Mime knows, it is the Volsungs. Next he asks the name of the sword Siegfried must wield to slay Fafner. Mime answers correctly and here we also learn that Mime is fully aware of who Siegfried is and who his parents really were. Wotan's last riddle is: who will forge Nothung anew? This Mime cannot answer: he cannot forge Nothung anew, so who can? As Mime panics, "Wanderer" leaves, having won Mime's head. He also says that one who knows no fear shall forge Nothung anew and that he leaves Mime's head to him who has never felt fear.

Mime is left alone in utter horror. His wild imaginings take over, and as Siegfried's figure shadows the cavemouth, he thinks it is Fafner who has finally come for him and screams in terror. Siegfried comes back to ask for Nothung, but Mime answers him that he cannot forge Nothung. Mime says there is one more thing Siegfried should learn: the meaning of fear - he promised Siegfried's mother (he says) he would teach young Siegfried the meaning of fear. He cannot teach Siegfried, but he knows one who can: Fafner. All right, says Siegfried, after I have seen this Fafner, I will leave you forever.

Siegfried decides to forge Nothung himself. As he forges the sword, Mime brews a drugged potion for him. Mime is happy again, he can see the fulfillment of his plans. The act ends with one mighty blow by Siegfried's Nothung, cleaving the anvil in two.

Act II

Alberich is watching Fafner's cave, Neidhoehle (the "Hate- hole"), for he wants to know where his precious Ring is. Wotan arrives, still posing as "Wanderer", but Alberich sees through his disguise immediately and calls him a shameless thief. Alberich remarks that Wotan cannot kill Fafner himself or else his Runestaff would break and his powers be lost forever and he also boasts about his own schemes of world domination. Wotan answers that Alberich need not mind him: he should worry about Mime instead. He also suggests that Alberich ask Fafner to give the Ring to him. As Alberich hesitates, Wotan wakes Fafner up. Wotan and Alberich tell Fafner about a strong boy with a sharp blade who is coming to kill Fafner, but wants only the Ring: if he gives up the Ring, he will be spared. Fafner ignores their words and goes back to sleep. Wotan laughs at this ingenious prank he pulled at Alberich and then leaves, warning about Mime one more time.

Mime leads Siegfried to Neidhoehle but dares not come near it himself. Even his terrifying descriptions of the Dragon do not scare Siegfried. Mime stays there waiting for Siegfried - Siegfried walks alone toward Neidhoele. He wonders what his mother was like - he has never seen a woman. He sees a beautiful bird - he carves a flute and tries to imitate its singing, but realizes his playing does not sound right. So Siegfried decides to give the bird a few notes from his hunting-horn.

As Siegfried blows the hunting-horn, Fafner comes out of his cave to investigate the noise. He says he wanted a drink and now he has found some food as well. Naturally, Siegfried does not want to end up as the Dragon's meal - he just wanted to "learn the meaning of fear". Fafner takes this to be bravado and a fight ensues presently. It is a brief fight: Nothung pierces the Dragon's heart very quickly.

Fafner, just before he dies, asks his slayer's name and tells his story to the boy. He also warns Siegfried about the evil intents of the one who lead him to Fafner.

Some of the Dragon's blood has been spilled on Siegfried's fingers and as he licks them - i.e. tastes the Dragon's blood - he realizes he can now understand the bird's speech. The bird tells Siegfried to take only the Tarnhelm and the Ring and leave the rest of the treasure (why the bird says this beats me: the bird must have been aware of the Ring's curse. Does the bird wish Siegfried's doom? TY).

Meanwhile, Alberich has reached Mime. They quarrel about to which one of them the treasure belongs. Mime suggests that they split the treasure: Alberich may keep his Ring and Mime gets the Tarnhelm. Alberich refuses: he could never sleep his nights safely if Mime had the Tarnhelm - thus he wants _both_ of the two magical artifacts. But just then Siegfried appears, carrying both the Ring and the Tarnhelm. Alberich curses and hurries off.

Now Siegfried can hear the bird's voice again: the bird warns him of Mime's treachery and tells him that he now can perceive what Mime is thinking in his heart.

Siegfried tells Mime that the teacher has failed: he could not learn the meaning of fear from Fafner. Mime tries to offer Siegfried a drugged potion, but Siegfried can read his mind as if it were an open book. He gets angry and slays Mime with one swift blow of his sword. He throws Mime's corpse in Neidhoehle.

Siegfried asks the bird if the bird knows where he could find a suitable companion. The bird tells him about Bruennhilde, who is lying in deep sleep, surrounded by a magic fire which can be penetrated only by one who knows no fear. Siegfried realizes how stupid he was, trying to learn fear and now follows the woodbird who will lead him to Bruennhilde.

Act III

It is night - the weather is stormy: there is thunder and lightning. Wotan, still disguised as the Wanderer, can be seen standing before a vault-like hollow in a rocky mountain. With a spell-song he wakens Erda the Earthmother herself, saying that he wants information. Erda is tired and asks why Wotan did not ask the Norns first. Wotan replies that the Norns can only perceive things: they cannot alter what is to come. Next Erda suggests that Wotan seek Bruennhilde's advice - she is very wise. But as Wotan tells about what has befallen on Bruennhilde, Erda is utterly bewildered. Wotan is disappointed in Erda's inability to give him any advice. He tells Erda about Siegfried, the _free_ hero and says that he will gladly accept anything all this leads to. He lets Erda fall back down to her slumber and leaves to meet Siegfried.

Siegfried meets Wotan at the base of the mountain on the top of which Bruennhilde lies. "Wanderer" (Wotan) interviews Siegfried about his newest heroic deed. But the disrespectful Siegfried talks to him so abusively that he eventually gets mad with anger. The furious Wotan blocks Siegfried's way with his Runespear and tells Siegfried to flee lest his spear break Nothung once more. Siegfried knows he has now met the person responsible for his father's death and as a vengeance breaks Wotan's Runespear in two with Nothung: there is a crack of thunder and Wotan (according to his own words) loses all his might. He flees and Siegfried ignores him, starting his climb up to Bruennhilde.

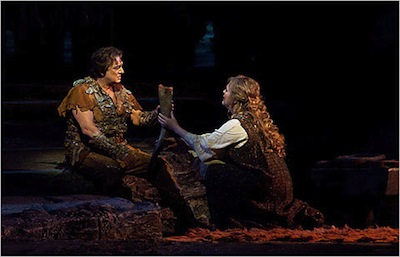

Siegfried goes through the enchanted fire and finds Bruennhilde there, thinking her to be a "man". But as Siegfried realizes she is definitely not a man, but something different, he shudders: for the first time in his life, he experiences fear. Unsure of what to do, Siegfried tries first to waken Bruennhilde, then kisses her. And by this kiss Bruennhilde is awakened.

Bruennhilde is ecstatically joyous to see that her awakener really is Siegfried. But as she sees her valkyrie battlegear and her steed, she is reminded once more of her glorious past. She realizes that she can never get that back again. But then the passion toward Siegfried takes over her, and she cares no more for Valhalla. They declare their love to each other and Siegfried has readily forgotten the fear he had just learned. Bruennhilde falls in Siegfried's arms, leaving her past life behind her, for good.

IV. Götterdämmerung (The Twilight of the Gods)

The First Prelude

The Three Norns are spinning the rope of fate. They are talking about things which are, have been and will be. We learn how Wotan lost his eye drinking from the Spring of Wisdom and how he carved his Runespear from a branch of the World-Tree Ash. Now the spring has dried up and the Ash has died, and Wotan's Runespear has been shattered. Wotan has ordered the dead Ash be cut down and the wood be piled around Valhalla as a great pyre which will one day be ignited by Loge. As the Norns are discussing Alberich and his Curse, the rope of fate snaps and is broken. The wisdom of the Norns is at an end and the Norns hurry to their mother, Erda.

The Second Prelude

A new day dawns around the Valkyrie Rock where Siegfried and Bruennhilde are. Siegfried can be seen in full armour in the sunlight. He wants to go wandering in search of new heroic deeds. Bruennhilde lets him ride her horse, Grane, and Siegfried gives the Ring to Bruennhilde, as a token of his faith. After a passionate farewell, Siegfried rides down the mountainside toward the River Rhine. Bruennhilde can hear the sound of his hunting-horn from the distance.

Act I

In the hall of the Gibichungs, lord Gunther asks his clever half-brother Hagen (whose father is Alberich) how could he win more fame and glory. Hagen says that Gunther should marry and only one wife would be noble enough for him: Bruennhilde who is surrounded by magic fire which only the bravest of heroes can penetrate. Gunther moans: he lacks the courage for such a task, why did Hagen have to mention that? Hagen says that indeed, the one with such courage is Siegfried - who is the person Gunther's sister, Gutrune, should marry. Gutrune thinks Hagen is jesting: how could she charm the bravest hero in the world? Hagen reminds her of a magic potion which would make Siegfried lose his memory and fall in love with the first woman he sees. Gunther admiresHagen's cleverness, but asks how they can find Siegfried.

Hagen replies that Siegfried is wandering, searching for new heroic deeds to be achieved and he might drop in here any day. Surprise surprise, that's when we hear Siegfried's hunting-horn. He has come to visit the castle and wants to see Gunther, Gibich's son. Hagen calls him by name (explaining later that of course everybody had heard of such a great hero and that's how he knew Siegfried). Siegfried wants Gunther to either fight with him or become his friend. Gunther, who evidently is not the bravest of living men, prefers to become his friend. Hagen leads Grane to the stables as Siegfried follows Gunther into the castle.

As Hagen returns, he inquires if it is true that Siegfried is really the owner of the Nibelung treasure hoard. Siegfried briefly describes his encounter with Fafner. Hagen asks if Siegfried took anything from the hoard. Siegfried shows him the Tarnhelm, which Hagen immediately identifies. He tells Siegfried of its powers: it allows its wearer to change shape at will and to travel from one place to another at the speed of his thought (this latter power was never mentioned nor used before). Siegfried also mentions the Ring and says "a most marvellous lady" is keeping it safe. Gutrune appears and gives a "welcoming toast" to Siegfried. It is the magic potion which makes Siegfried lose his memory and fall madly in love with Gutrune. The unfortunate Siegfried drinks the toast "for Bruennhilde" [he speaks these words "aside" so Gunther does not know that Siegfried's beloved is none other than Bruennhilde].

Siegfried wants now to marry Gutrune. When hears about Gunther's "beloved", Bruennhilde, and the fires which surround her rock, his mind is struggling to throw off the spell of amnesia, but up to no avail. He devises an ingenious plan: he will use the magic of the Tarnhelm to disguise himself as Gunther and win Bruennhilde for Gunther, if Gunther lets him marry his sister, Gutrune. It's a deal, says Gunther and Hagen makes Gunther and Siegfried swear an oath of bloodbrotherhood before Siegfried leaves to conquer Bruennhilde for Gunther. [It is indeed possible - even likely - that Gunther never realized Bruennhilde was Siegfried's beloved. Had he known that, he might not have been so eager to take part in this plot]. Hagen sits on watch, waiting for Siegfried's return and when left alone, reveals his true plans: he is only interested in the Ring and is using Siegfried and his half-brother, Gunther, only as pawns in his master scheme.

Meanwhile, Bruennhilde has a visitor: her Valkyrie sister, Waltraute, rides in on a flying Valkyrie horse with a clap of thunder - against Wotan's orders. She tells Bruennhilde the lates news from Valhalla: how Wotan no longer goes wandering, but just sits on his throne, doing nothing. Wotan has said that only if Bruennhilde would give the Ring back to the Rhinemaidens, the gods and the whole world would be freed from its Curse. Bruennhilde has no intention of throwing her precious Ring away and she angrily tells Waltraute to leave. Waltraute, seeing that her pleads can only be refused, leaves predicting some horrid fate for Bruennhilde, gods and everyone.

Bruennhilde hears a horn - she thinks Siegfried is coming back. But the figure who emerges from the fire is Gunther (actually Siegfried in Gunther's guise). He imitates Gunther's voice and informs the terror-stricken Bruennhilde that she is now Gunther's wife. He takes the Ring from Bruennhilde's finger. He decides to spend the night here, but proclaims that Nothung will guard his oath of bloodbrotherhood during the night.

Act II

Hagen has fallen asleep. His father, Alberich, appears in a dream vision. He tells Hagen that he must oppose Wotan's kin and gain the Ring no matter what price. He also says that the Rhinemaidens must not get the Ring or all is lost - and that Bruennhilde might be wise enough to do that. As Alberich gets Hagen's promise, he disappears and Hagen wakes up.

Just then Siegfried appears, using the Tarnhelm's power of teleportation. He speeds to Gutrune, telling her that she can now marry Siegfried: he has completed his part of the bargain.

Hagen blows into a cowhorn, summoning the Gibich vassals, who think there is an attack or some other danger. This is, however, only a practical joke: he tells the alarmed vassals that there is no danger and they should now prepare a great marriage feast. The vassals love Hagen's joke.

As the crowd watches, Bruennhilde and Gunther come from a boat. Bruennhilde is shocked, seeing Siegfried and Gutrune together. Then she notices the Ring on Siegfried's finger and says it was Siegfried who took the Ring from her. Siegfried is confused: he can now remember slaying a Dragon and thus winning the Ring. Hagen suggests to Bruennhilde that Siegfried has played some trick. Bruennhilde screams: trickery! treachery! The crowd is getting nervous. She even claims that Siegfried forced delight from her, at which Siegfried decides to swear a new oath that he has spoken true. Hagen offers his spear for the oath. Siegfried swears: if I have sworn falsely, let yours be the blade that pierces me. Suddenly, Bruennhilde also places her hand on the spear and blesses the blade for this purpose, for, she says, falsely has Siegfried sworn indeed. Siegfried feels a bit uneasy whispers to Gunther that maybe the Tarnhelm hid his features only partially and instructs Gunther that he should let Bruennhilde be in peace for some time so that she can learn to accept her fate.

Later, Bruennhilde, Hagen and Gunther are together. Bruennhilde wonders what has happened to Siegfried - what devil's trickery has made him betray her? Hagen offers to avenge her on Siegfried, but Bruennhilde doubts his combat prowess: a single flicker from Siegfried's eyes would suffice to make Hagen's courage falter. Surely, asks Hagen, he would still be vulnerable to his spear because of the false oath he swore on it? Bruennhilde says that she has protected Siegfried with magic which makes him invulnerable to any weapon - only his back she spared protection as she knew Siegfried would never turn and run from any combat. There shall my spear strike, declares Hagen. Gunther is desperate: the events have put him into a terrible shame. Hagen's answer is that only one thing can restore his honour now: Siegfried's death. Gunther falls silent and hesitates, but Hagen makes him come around with a hint of the all-powerful Ring which Siegfried is wearing. Bruennhilde, Hagen and Gunther decide that Siegfried shall die. Aside, Hagen tells Alberich to summon the Nibelungs to serve him once more: the hour of their dominion is at hand.

Act III

The Three Rhinemaidens are singing and swimming in the River Rhine, as Siegfried arrives. He is hunting, but has lost his prey. The Rhinemaidens spot the Ring and try to persuade (almost seduce) Siegfried into giving it to them. For a moment Siegfried holds the Ring in the air and is indeed going to give it away, but as the Rhinemaidens warn him of the dangers which he will meet if does not yield the Ring, he simply declares he does not care for his life. The Rhinemaidens swim away calling him a madman - and they prophecy that the Ring will today go to a certain lady, who make a more reasonable decision. Siegfried ignores them: first seducing, then threatening, but it did not work - not for him.

Siegfried meets the rest of the hunting party: Hagen, Gunther and some vassals. Gunther is very depressed as Hagen mixes a drink for Siegfried, who also offers the drink to Gunther. To brighten Gunther, Siegfried decides to tell a story from the years when he was but a boy. He now remembers Mime and how he could understand the bird which told him not to trust Mime - and how he eventually slaughtered Mime. Hagen gives him another drink which will "waken [his] memory more clearly". Now Siegfried tells the others how he found Bruennhilde - Gunther is shocked: Siegfried remembers now everything [and what's more, his beloved turns out to be none other than Bruennhilde - Gunther may not have suspected this earlier]! Two ravens fly up and circle above Siegfried, then fly away. Hagen asks him if he was able to understand what the ravens said. Revenge they cried to me, says Hagen, and plunges his spear in Siegfried's back. Siegfried falls down. Gunther and the vassals are terrified and ask Hagen what did he do that for. Hagen still maintains it was a vengeance. Siegfried opens his eyes and still sees a vision of Bruennhilde, then dies.

Siegfried's corpse is taken to the hall of the Gibichungs. Hagen tells Gutrune that Siegfried has fallen prey to a wild boar. Gutrune accuses Gunther of murdering Siegfried, but Gunther replies that Hagen was the "wild boar". Hagen confesses murdering Siegfried, but as Gunther proceeds to take the Ring, he attacks Gunther and strikes him dead, saying abruptly: "Give the Ring here!". Now everyone present is shocked, as Gunther is killed by his own half-brother. Nobody makes any attempt to stop Hagen as he now proceeds to take the Ring - but miraculously Siegfried's corpse raises its hand as Hagen draws near. Hagen is terrified and dares not go any nearer.

Now Bruennhilde enters: she has heard everything and now knows what all was about. She makes it clear that Siegfried belonged to Bruennhilde all the time and Gutrune admits that.

Bruennhilde instructs the vassals to pile logs into a funeral pyre and leave Siegfried's corpse atop the pyre. She understands that it was not in fact Siegfried who deceived her as he in turn was betrayed himself and thus forgives Siegfried and mourns her loss. She wishes him peace saying that she knows now everything. She takes the Ring and says that the fire that soon consumes her will cleanse it from the Curse and then the Rhinemaidens can fetch their gold from the ashes. She puts on the Ring and takes a torch from one of the vassals. She tells Wotan's ravens to fly home past the Valkyrie Rock and bid Loge, who is still there, to go to Valhalla: the downfall of gods is nigh. He hurls the torch into the pyre with the words "Thus do I throw this torch at Valhalla's vaulting towers!" (DG translation). The wood catches fire rapidly. Bruennhilde mounts her steed, Grane, and speaking a last greeting to Siegfried she rides into the blazing pyre.

"The flames instantly blaze up and fill the entire space before the hall, seeming even to seize on the building. In terror the women cower towards the front. Suddenly the fire falls together, leaving only a mass of smoke which collects at back and forms a cloud bank on the horizon. The Rhine swells up mightily and sweeps over the fire. On the surface appear the three Rhine-daughters, swimming close to the fire-embers. Hage, who has watched Bruennhilde's proceedings with increasing anxiety, is much alarmed on the appearance of the Rhine- daughters. He flings away hastily his spear, shield and helmet, and madly plunges into the flood crying 'Keep away from the Ring!'

"Woglinde and Wellgunde twine their arms round his neck and draw him thus down below. Flosshilde, swimming before the others to the back, holds the recovered Ring joyously up.

"Through the cloud-bank on the horizon breaks an increasing red glow. In its light the Rhine is seen to have returned to its bed and the nymphs are circling and playing with the Ring on the calm waters.

"From the ruins of the half-burnt hall, the men and women perceive with awe the light in the sky, in which now appears the hall of Valhalla, where the gods and heroes are seen sitting together.... Bright flames seize on the abode of the gods; and when this is completely enveloped by them, the curtain falls." (Wagner's stage directions)

The End

©2014 by author - All Rights Reserved

Used here with permission