Chapter 4

Western Art Music to 1600

Medieval Music

The Middle Ages is the longest of the chronological style periods. The traditional date for the beginning of the Middle Ages is the fall of Rome in 479 AD. Medieval music then, includes the music of the 6th through the 14th centuries.

Although music was indisputably an important part of life during the so-called Dark Ages, it is the music of the Gothic era that we know most about. The simple reason for this is that pitch-specific musical notation only dates from around the milenium.

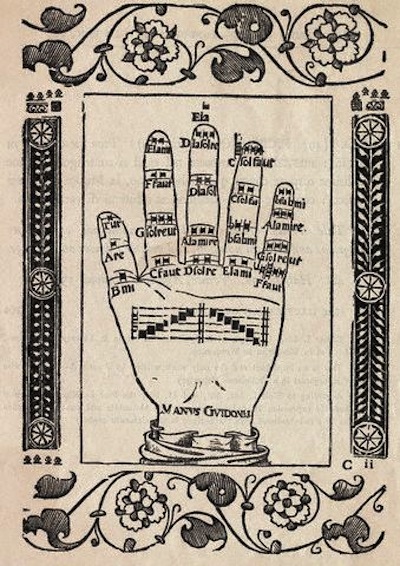

Developed by Guido d'Arezzo, the "Guidonian Hand" was a visual tool used in teaching sight-singing to singers.

The first notated repertoire of music in Western culture is plainsong, also called Gregorian chant after Pope Gregory I, who legend tells us composed many of these liturgical songs. In truth, the pope did not compose plainsong; the lack of a pitch-specific notation would preclude that. More likely, he initiated and supervised an effort to collate the large body of liturgical song that had already accumulated by the 7th century.

For the sake of clarification, plainsong is a broader term than Gregorian chant. It encompasses Ambrosian chant from Milan, Gallican chant from France, Coptic chant from Egypt, and Mozarabic chant from moorish Spain. Chant scholars investigate all these sources, but Gregorian chant is the classic liturgical music of the Roman Catholic Church in most areas of the world, including America.

Where in America does one go to hear Gregorian chant sung? Certainly not in your local parish church. Since Vatican II (1962-65), most congregations have moved in the direction of American popular styles for their liturgical music. With the exception of monasteries, a few large churches, like cathedrals and basilicas in major cities like Chicago and New York with paid choirs, plainsong is no longer used in worship.

Although it is hard to find live performances of chant, there are many recordings available. The music is very relaxing to listen to, even if you don't understand the Latin text. Generally, it's not the words people are interested in, it's the music. The Dies Irae ("Day of Wrath"), from the Mass for the Dead (Requiem) is a good example. The text is not a very soothing one; it speaks of the Day of Judgment when the earth will be consumed by God's anger. It's a musical (but not chronological) analogue to Michelangelo's famous painting on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. But the music is still serene. What makes it so? What are the characteristics of chant?

A famous and beautiful myth about the origin of plainsong tells us that a dove came down from heaven and sang into the ear of Pope Gregory the Great. These sacred melodies, dictated by the Holy Spirit, were written down by Pope Gregory's scribe and became known as Gregorian Chant.

painting: St. Gregory by Matthias Stomm (1600-1652)

While this music is arcane, it is not abstruse. It still has an appeal, both as functional liturgical music and as pleasant facilitator to relaxation. It also has scholastic value, because the principles of melody established in plainsong continue to influence composition through the 19th century. Composers of the Renaissance often borrowed and paraphrased plainsong melodies in their masses and motets. We'll investigate this more later.

Secular Music

If you stop reading here, you'll have the impression that the only music heard in the Middle Ages was plainsong. Of course, that is not the case. Secular music played an important role in medieval life. People sang and danced and played instruments, just as they do today. Of course, not very many people were trained to read and write notation, so most of the musicians played by ear or memory. There are no scores of this popular music that allow us to reconstruct the sound with any certainty, the way we do in the Renaissance. But we know from contemporary accounts that music was present at all kinds of secular events from weddings to jousting tournaments to coronations. There were even bands of peripatetic musicians and actors known jongleurs who traveled from village to town entertaining the common and well-born alike.There is a repertoire of secular monophony that we know a lot about, largely because the composers and performers came from a social class that taught and encouraged them to write down their music. They were theTroubadours, and their relatives the Trouveres and the Minnesingers. These are the 12th century composers of chivalric song who glorified the women they loved and immortalized them in verse. The art of courtly love certainly included music.

Polyphony

Also in the Gothic era, notably in England, Spain and France, examples of polyphony begin to appear. Polyphonic music features the combination of two or more melodies to form musical texture (fabric). Early polyphony, known as organum, is very simple with one voice simply shadowing the other at a predetermined interval, usually a perfect fourth or fifth. It sounds hollow. There is very little rhythmic interest or contrast between the voices. As the practice became more advanced, composers attained a very high level of proficiency, combining an active, florid melody with a more static one. To do that, they required a more advanced system of rhythmic notation.The 13th century is notable for a great creative flourish at the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris. Sacred music there under the direction of two famous musicians, Leonin and Perotin, became more sophisticated, especially in the area of rhythm. They developed a system that permitted accurate notation of fairly complex rhythmic patterns. Early polyphony flourished alongside plainsong rather than replacing it. The second half of the century brought about the genre called the motet, which combined secular French texts with sacred Latin words in the same song. The Gothic motet is different from the Renaissance motet, which is discussed in the next lecture.

In the 14th century, art music takes on an even greater sophistication. Composers like Guillaume de Machaut (1300-1377) exploit developments in rhythmic notation to produce extremely complex sacred and secular works. Mathematical proportions, which had figured into the calculation of pitch since ancient Greece, began to dominate the structure of music, permitting composers to produce much longer works.

The most famous of these was Machaut's Messe de Notre Dame, a complete musical setting of the Mass Ordinary. The Ordinary is the text of the Mass that remains constant throughout the liturgical year. For example, the Sanctus (Holy, Holy, Holy) is the same for Christmas or Easter or the Feast of Corpus Christi. This is in contrast to the Proper texts, which vary according to the liturgical occasion. The obvious advantage for a composer in setting the Ordinary is that the music can be used at any time during the church year rather than being reserved for a particular season or feast day. The Mass will become the most important musical genre of the Renaissance. We will examine that in more depth in the next lecture.

Renaissance Music

When speaking of music, the Renaissance is generally understood to refer to the 15th and 16th centuries. It is a classic period in that it seeks the goals of classic art. The word ORB is a useful mnemonic aid for these characteristics. Classic art is:Objective. It deals more with ideas than ideals, more with thought than feeling, more with the cognitive than the affective creative impulse.Restrained. Classic art is never extravagant, exaggerated, or hyperbolic.Balanced. The emphasis is on form, symmetry, and structure rather than on the expression of feeling at the expense of those things.Classic studies center around classical languages and culture of Ancient Greece and Rome. The academies of the Renaissance sought the rebirth of this perspective.

Romantic art is, by contrast, subjective, extravagant, and expressive or emotive in nature. The Middle Ages represent the romantic point of view, especially the Gothic era.

The field of Renaissance music is one that has inspired much scholarly investigation. A very famous book on the subject by Gustav Reese

Most of this music is vocal and much of it is sacred, but there is also much secular music, and more surviving instrumental (mainly dance) music than you might imagine. Nearly every major European library contains impressive collections of part books and scores in manuscript. Another important aspect is the beginning of music printing around the year 1500,

The Mass

The principal sacred genres of this time were the Mass and the motet.The Motet

Like the Mass, the Renaissance Motet is a polyphonic sacred work in Latin meant to be sung by a choir of 4-8 parts, a cappella. That means, literally, the way they do it in the chapel; and chapels of this period usually had no organs, so it means unaccompanied. Although the musical style of Mass and Motet are the same, the Motet differs from the Mass in that it is a single piece rather than a set of six. Motets are used mainly for the items of the Proper, the part of the Mass that varies in text according to the liturgical occasion. For instance, the Introit for Christmas is "A child to us is born," while the one for Easter is "He is risen!" These texts are always in Latin and usually taken from Scripture or the prayer book.This music is not easy to sing and definitely requires trained musicians and ample rehearsal time. In the Renaissance, all-male choirs were maintained by wealthy aristocrats in their private chapels and by a few cathedrals and basilicas. Often the composers were singers in the choirs or even the directors. Masses and Motets were not music that the congregation could participate in, and this is exactly what reformers like Martin Luther objected to. Oddly enough, Luther was a musician and a great admirer of the greatest composer of the 15th century, Josquin des Prez, who, incidentally, was a contemporary of Christopher Columbus (In 1492. . .). Josquin was from the area now known as the Netherlands but, like most great musicians of the period, worked in Italy for a good portion of his career.

Palestrina

The greatest composer of the late Renaissance is Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, who flourished in Rome during the period often referred to as the Counter-reformation, the second half of the 16th century. Palestrina composed over a hundred Mass settings and as many Motets and served all four of the most important churches in Rome. His influence on succeeding generations of musicians cannot be overstated because his style later came to be a paradigm for composition of polyphonic vocal music.By the 18th century, all composers were trained in the contrapuntal practice deduced from studying the works of Palestrina. Mozart studied it with Padre Martini, Beethoven studied it with Haydn, and so forth. It is still taught today in every college and conservatory in the Western world. This makes Palestrina one of the most influential composers in the history of music.

Secular Music

While Josquin wrote both sacred and secular music, Palestrina wrote primarily sacred polyphony. But there was a thriving culture of secular art music throughout Europe and England. The most important genres are the madrigal and the chanson. If you were in a really good choral program in high school, you probably sang some madrigals by composers like Thomas Morley. English madrigals were all the rage around 1600. They are also polyphonic but usually were sung by one singer on a part, rather than by a choir. The texts were in the vernacular and dealt mainly with love, often unrequited. Madrigals were usually copied or printed in part books and sung sitting around a table at home, mainly for the amusement of the singers.Madrigals were very popular in Italy even before they were brought to England, and the Italian texts of these songs were sometimes the work of great poets, like Petrarch. The art of part singing was cultivated among the cultured people of cities like Florence, and men and women sang them together in contrast to the all-male ensembles of the churches. Composers like Luca Marenzio wrote some little masterpieces in this genre. A popular example of this is Scendi dal paradiso, Venere.

Secular polyphonic music was also very popular in France, where the chanson flourished. It was much like the madrigal although generally more homophonic

Conclusion

The recording industry has done a great service to the revival of Renaissance music. Although the classical segment of the market is only about 1% and early music a small corner of that, there are now available recorded examples of all the major composers in all the genres of the period. Unless one seeks out live performances of early music in major cities or attends a university with a thriving collegium musicum, recorded performances are likely to be the only ones heard.So where can you go to hear live Renaissance music performed? Besides the two places just mentioned, there are few. Modern churches don't use polyphonic sacred music. It requires a professional choir and lots of rehearsal; and besides, modern tastes don't call for it. In fact, the function of this music has now changed. No longer functional worship music, it has become concert music presented to a select taste by groups of specialists.

The market niche may be small, but the aesthetic value of the music remains great, and its historical importance to Western culture cannot be overestimated.

Chapter 4 Music for Listening